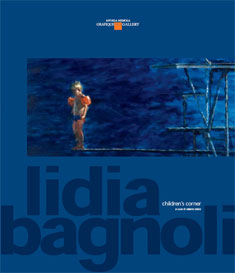

children's corner

-

Blu gioco -

Gioco -

giocoblu.jpg -

giocorosso.jpg -

giocoverde.jpg -

grandegioco1.jpg -

grandegioco2.jpg -

grandegioco3.jpg -

grandegioco4.jpg -

sarasara1.jpg -

sarasara2.jpg -

sarasara3.jpg -

sarasara4.jpg

children’s corner

Angela Memola - Grafique Art Gallery - Bologna december 2008“The only existing things are those my eyes see when they are open, and even more when they are closed. Great sensitivity is what is more needed.

Thinking of anything in the world, not only of the questions you have always asked yourself, as an enigma… Seeing the enigma in things which are generally considered as irrelevant”.

Giorgio de Chirico

The relationship connecting art to the childhood’s world is very deep and represents one of the major cultural themes of the XX century.

Developed mainly by the artistic avant-gardes, last century particularly insisted on the artistic creation as the capacity of re-inventing the perception of reality, of taking an innocent, and therefore quite new, glance at the world’s events, starting from the pure and naïve vision which is typical of children.

As a matter of fact, the historic avant-gardes, frm Futurism to Surrealism, were exactly those who re-evaluated the children’s world as an universe of endless potentialities, which are then altered and forgotten by the grown-ups. Looking at the children and at the universe they live in has become an element of control of art itself, a point of view over something anarchic and unsettled which, in any case, belongs entirely to life.

Therefore, not only has the XX century drawn a comparison between the artist and the child, but it has also remarked the importance of play, for instance, which constitutes an aspect connected to learning and essential to the creation of a personal Weltanschauung. Enjoying is learning because it is a simulation of life, it is an element common to human beings and animals, and in this simulation a space is opened for whetting the children’s fantasy and symbolic capacity. Art and ludic activities are considered as a pillar of knowledge, and their organization is seen as a language of its own.

But an aspect of the play and of the observation of children is also connected to their movements: even in gestuality, in attitudes, in glances, in proxemics in general, there is a childhood. And this is what Lidia Bagnoli perfectly detects and transposes into painting, because she can read in the depth of an action which is often just auroral, uncertain, not completely defined yet. It is not the gesture, but the potential state of that gesture, the paintress is interested in. And this happens because children often have great difficulties in perfectly reproducing the movement they decide to carry out, exactly because they can not master it completely. Bagnoli’s mellow, dense, yet quick

painting often represents children immersed in their daily life, in normal actions, or carrying out physical gestualities such as diving, running and other sporting and ludic activities. There is a deep interest in anatomy together with a psychological introspection showing childhood as a problematic moment of birth and learning.

This study also comprises the “portraits” of adolescents set in urban landscapes which made the artist known to art estimators. They are a human presence who, in relation to the town and to the spaces of urban aggregation, always seem to be looking for something, searching for a way, for one of a thousand possible paths. They are, after all, symbolic characters of a Bildungsroman which always saw the adolescent, namely the person at the final stage of his/her childhood, focused on the knowledge of the world, on its surprises and suggestions.

So, not only is the paintress interested in this dawning state of personality, of attitudes, of search for a “position” in the world, but also in a study of gestures which is very much related to classic painting, wherein the artists feel the need to look for the anatomy underlying the shapes. In some cases, several characters or several gestures of the same character are enclosed in a single picture, to witness the stages of the research, the progress of the study carried out by the paintress for this cycle of works.

Lidia Bagnoli’s is a grown-up painting, not one following the lightened schemes of the avant-garde which devoted itself to children’s marks and pictures as a new positive and primitive source for the artistic research.

Her figuration always contains some existential features without renouncing to the painting’s basic need of catching the different aspects of life, the multiple attitudes of human beings, something eluding the eye but settled in the image.

Her figuration evokes the icasticity of the drawing, but plunges the subject in the thickness of the colours, in an attractive and dense material, nonetheless remaining faithful to a painting which is at the same time descriptive and analytical, but never didascalic.

On the other hand, present painting does not seem to look for differences with regard to the sources of inspiration. Bagnoli does not exaggerate with details, prefers an original point of view, a composition with visual impact, a neat chromatic contrast, and seems to belong to a generation which still esteems a lyrical and gestual figuration. Painting does not express indifference towards the world, but a passionate adhesion and an empathy to participate in it with her own tools.

But that is exactly the point: also contemporary artists feel the need for an active confrontation with the past, even in those existential and very free forms of neo-expressionist painting like the post-conceptual, which finds in these works a strong and active helm. Childhood and adolescence in Lidia Bagnoli’s works are not a place of practices as sugary as far away from reality. Nothing is simple but at first sight, her “figure pictures” demonstrate how wrong we are when we do not judge reality from appearances, thus preferring an expressionist figuration revisited from the Eighties. Beside her existential root, you feel a special strength in her work, provided with a charge of intimacy

which never becomes sentimentalism. Fate is hinted to as a reference to forces keeping together beings and shapes.

The impossible is eternally repeated because it is not clear what is actually possible. As a matter of fact, although painting is timeless, the human capacity of wonder remains inexhaustible. It is true that nothing

is repeated in itself, nothing can be the same of what has been in spite of an apparent isomorphism.

As Silvia Evangelisti smartly wrote, “it is like life were, for the painter and for the observer, beyond a diaphragm, on the other side of a glass, beyond an imaginary window from which they watch the scenes of the world. And, on the other hand, the theme of the window (in this case, real) is loved and frequently visited by Lidia Bagnoli in many of her works: the window from which the sunlight enters like a stripe of colour; the window which opens to the outside, to the green, to air, to life.” Reality is measured by distance. Distance shows the world in a real world, although not exactly ordered and defined. But this is precisely the characteristic of painting which, unlike other arts like photography,

always needs a temporal processing, a concrete decision on the making and unmaking of vision. Painting is reflective, both because it reflects the world and because it needs time to process the images according to psychological and perceptive coordinates matching the meaning the artist gives to his/her work and his/her research. This is the observing perspective of the artist, who chooses a personal point of view and from this surveys the world in its succession of events, persons, seen and unseen things. But persons can not exist without a tale, and therefore the meaning of everything resides in becoming something connected to others or to landscapes you pass through, even

just for once. The play and that period always hardly definable which is childhood are a further false move of Lidia Bagnoli towards the inexhaustible, endless, fascinating reality we usually call “daily life”.

Valerio Dehò

[

[